(Last Updated On: 10th January 2019)

In much of Edinburgh’s centre, it’s impossible to walk more than a few steps without falling over a statue or monument commemorating the city’s great residents of the past. But there’s been discussion lately about the fact that only two of these are of (named) women. Two. In the whole of Edinburgh. Which is even more incredible when you learn there are on the other hand three statues erected to (male) animals. Now, while I leave that little factoid to marinade in the back of your mind, this post is actually about the witches of Edinburgh.

As you’re leaving Edinburgh Castle and begin to head down The Royal Mile, most people won’t notice The Witches Well on Castle Hill. Or if they do, they might just think it’s a water fountain or, in the warmer months, an ornate flower pot. It is actually the only memorial in Edinburgh commemorating the deaths of hundreds of people – largely women – during the witch trials of the 16th, 17th and 18th centuries.

Edinburgh Witches and History Walking Tour

Now, the Scots are fiercely proud of their history, and rightly so. In the few hundred years after the first witch trials they contributed significantly to the world in science, medicine, technology and literature. But while you hear a lot about the brilliant Scots of the Industrial Revolution and Enlightenment when you visit Edinburgh, the witch trials are, understandably, not so widely spoken of. But they are significant nonetheless.

After the creation of the Witchcraft Act of 1563 – which made consulting with a witch or practising witchcraft a crime punishable by death – more people were tried for being or cavorting with a witch in Scotland than in any other country in Europe. The exact numbers are unknown, but thought to be somewhere between 4000 and 6000. Of those, around 1500 were then killed, with Edinburgh executing more people than any other city in Scotland – somewhere between 300-400.

The North Berwick Witch Trials

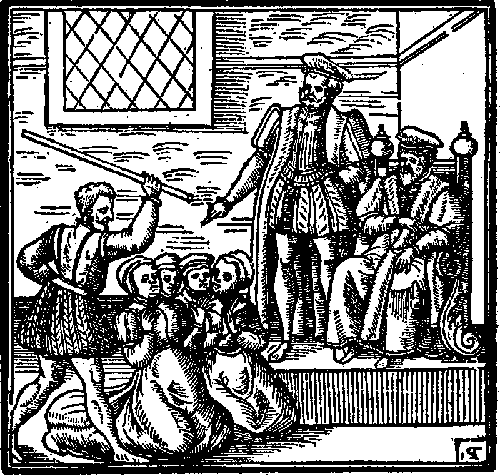

The first and perhaps best known of the Edinburgh trials were The North Berwick Witch Trials of 1589. They were largely the making of King James VI, who was thought to be consumed with paranoia that women all over town were colluding and together could gain the political power to overthrow him.

When bad weather and rough seas forced the delay of the King and his new wife Anne of Denmark’s return to Edinburgh from Copenhagen, the Danish ship’s Admiral announced the voyage had been cursed by a Danish woman who was a witch. The Admiral by the way, had recently had a run in with a Danish official, the husband of this woman. Hmmm, see what he did there?

When King James, now sheltering in Norway and still waiting for storms to die down, heard this, he jumped on the bandwagon, announced that witches in Edinburgh had cursed him and went about setting up his own trials. A local Edinburgh maid, Geillis Duncan, became the perfect scapegoat after her employer noticed her natural healing gifts. After being tortured in jail (most likely through sleep deprivation), Geillis confessed and then named others who were also witches. They in turn were tortured and confessed more names, a vicious circle that would be repeated time and again at major trials all over the world.

In total, the North Berwick Witch Trials ran for two years, by which time more than 70 people had been accused.

The Witches’ Well

The Witches Well is not really a well. It’s actually a fountain and a plaque, and it’s located on the spot where those found guilty of witchy things were strangled, then hanged, or burnt alive. The fountain was erected in 1894 on the side wall of what is today The Tartan Weaving Mill. Artist John Duncan was commissioned by his friend, sociologist, botanist, urban planner and all round cool dude, Patrick Geddes. Seriously, Geddes is fast becoming my Edinburgh hero. For a man in the 19th century to feel that strongly about the need to do something to mark the terrible fates of these women, when today Edinburgh still only has two statues honouring women properly, is remarkable.

The cast iron fountain is quite ornate, if a bit repetitive with the symbolism. It depicts a snake wrapped around two witches heads, one head representing good, the other evil. In symbology too of course, snakes are commonly used to represent both good and bad. There’s also some foxglove twirled around them all, which is symbolic for – bet you can’t guess – yey, good and evil. Foxglove, though poisonous, can also be used for medicine if you know what you’re doing. The plaque came later, in 1912.

Douking

You may have heard of this in books or films and wondered if it was just a myth, but ‘douking’ or ‘ducking’ accused witches in bodies of water to see if they drowned or floated was actually a practise that went on in Edinburgh. Floating means you’re a witch and would be killed. Drowning, well that meant you were innocent. Mmmm, ummm, what? At least your family will have known you were innocent. The ducking was done in the N’or Loch, the body of water that used to run where Princess Street Gardens is located now.

The Witchery

Just a little further down The Royal Mile from The Witches Well is The Witchery restaurant and boutique hotel, or as I like to call it, Edinburgh’s most expensive place to eat and sleep. Considering the horrible fates of these women, I don’t see how this is a fitting tribute to them, but in any case, if you have plenty of cash to splash, its rooms are over the top opulent and the food is meant to be delicious (I cannot confirm or deny this as I am not a millionaire).

Witch Statue in Prestonpans

Andy Scott, the artist who designed the Kelpies in Falkirk, was commissioned to design a statue in Prestonpans, a small fishing town just outside Edinburgh, for the 81 women convicted of witchcraft there. As statues go, it’s quite beautiful, but it’s located right next to a children’s playground in the middle of a non-descript housing estate. There’s nothing there to explain what it is supposed to be commemorating and it wasn’t even given a name. To me, it doesn’t really do justice to the women’s memories either.

Extra Stuff:

The British parliament repealed the 1563 Act in 1736, after which, being charged with witchcraft just had you labelled a con-artist and fined.

The last woman tried and jailed for witchcraft in Scotland was Helen McFarlane in 1944. She was a medium and found guilty of making fake ectoplasm to fool her clients. She though only got some jail time.